The Imprecision of Language

Unfortunately, language is fluid and so the meaning of words tends to change over time. Musical words and terms are no different. Very often genres of music start with very broad meanings, but over time come to have quite specific meanings. And this is precisely what happened to the musical term ‘Blues’. Today, when someone says ‘let’s play a blues’ they generally mean two very specific things. They want to:

- Use the 12 bar blues form; and

- Use the blues scale to improve

But originally, the term ‘Blues’ was much more general and vague.

A Short History of the Blues

The Blues began to emerge as a distinct genre of music in the late 19th and early 20th century. It evolved out of the field holler and work songs of African slaves in the South of the US. It took its name from the word ‘blue’, meaning feeling sad or depressed. Now, around this time the guitar became widely available for the first time in the rural South of America. As a portable instrument, it was embraced by many African American musicians at the time. So the early style of blues, called ‘country blues’ or ‘delta blues’, was generally performed by a single male musician playing guitar and singing. Think of musicians like Robert Johnson or Lead Belly.

Slavery was officially abolished in the US in 1865, so needless to say most of these black musicians were not formally educated in the intricacies of Western Harmony and music theory or proper technique. This meant their music was quite simple, repetitive, rough and primitive but also emotional, straight from the heart and raw. These musicians used tuned their guitars in unusual ways and played them by pressing knives and bottlenecks against the strings. They also song emotively without worrying about playing the Major Scale in equal temperament. Because of their lack of formal education they often played and sang ‘out of tune’ – that is, they played and sang ‘blue notes’.

So blue notes, originally, actually referred to out of tune notes, or microtones, or notes located between the 12 notes of western music. Over time the Blues was picked up by professional musicians and formalised. As this happened musicians had to fit these out of tune microtones into the pre-existing Common Practice western musical system. And so this approximation meant that ‘blue notes’ became the ♭3, ♭5 and ♭7 used over a Major Triad, which western music theory said were ‘wrong’ and therefore ‘out of tune’ – and so we lost the microtones, or the ‘true’ blue notes. Though, of course, guitarist and singers can and do still hit these microtones by bending their notes. But, unfortunately, that’s not possible on a piano. And these out of tune blue notes could be used as an emotive device, like any other musical device.

The blues was very largely improvised. This meant that the form was loose and free – they didn’t just stick to 12 bars – some were longer and some were shorter. They were, after all, untrained musicians so their music was a little bit unstructured. You only need to look and listen to early blues songs by people like John Lee Hooker or Blind Willie Johnson to hear their non-12 bar structures. In fact blues songs would often just sit on one chord for the whole song. It was only later in the 1910’s and 1920’s, when blues became more popular and was taken up by professional musicians like Ma Rainey that the blues began to become more codified and standardised. W.C. Handy, known as the father of the blues, was one of the first people to start writing down blues songs he heard in sheet music and is credited with giving the blues it’s contemporary twelve-bar stanzas with the standard chord progression we all know. He was really instrumental in taking the rural and regional blues style and popularising it across America.

Lyrically, the blues consisted of a three-line stanza, with the first line being repeated in the second line to allow extra time to think of a third line that rhythmed. It was also generally in the first person and so very personal. This was different to earlier folk songs which were generally in two or four line stanzas and sung in the third person.

So the blues has evolved from:

| Element | Early Country Blues | Contemporary Blues |

|---|---|---|

| Form | Varied, irregular, improvised | (Generally) 12 bars |

| Chord Progression | Varied, complex, irregular | Primarily: I, IV, V plus a few other chords: I7♯9, ♭IIIMaj7, IV7, ♯IVdim7, V7♯9, ♭VII7. |

| Scale | Varied and included microtones | Blues scale |

| Blue Notes | Microtones | ♭3, ♭5, ♭7 |

Blues Harmony vs Western Harmony

So that’s a short history of the blues, and I tell you it because I want to illustrate that the Blues did not come from the western music tradition and therefore does not conform to our western rules of harmony.

Now there are lots of differences between blues and classical music. The two obvious ones being:

| Traditional Western | Blues |

|---|---|

| Composed | Improvised |

| Straight | Swung |

Right, that’s a pretty self-evident and boring analysis. But more interestingly, the blues breaks a number of Common Practice ‘Western’ Rules of Harmony. Key differences between ‘Western’ Harmony and Blues Harmony are:

| Traditional Western | Blues | Possible Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Harmony V7 resolves to I | Non-Functional Harmony V7 does NOT resolve to I Tonic dominant chord (I7) | Use borrowed chords: I7 – Mixolydian Mode IV7 – Dorian Mode |

| V-I Perfect Cadence most important | IV-I Plagal Cadence most important | May have been influenced by Church Hymns |

| Never combine the Maj3 & min3 | Combine the Maj3 & min3 | min3 = #9 over V7 Maj3 = 'real' 3rd |

| ♮11 over V7 not allowed | ♮11 over V7 allowed | Playing outside |

| 12 notes | Microtones | Playing outside |

| Leading tone resolves to Tonic | No leading note in the Blues Scale b3rd resolves to Tonic | Playing outside |

Now, we can think about this ‘Blues Harmony’ in three different ways:

- Blues harmony is wrong (western harmony is right) and thus blue notes and all the other things I just listed are intentional dissonances that break the rules of harmony, like playing ‘outside’ but never resolving.

- Blues is a mix of major and minor tonality – it is really in a major (or minor) key like any other western song but just uses a lot of modal interchange. So the blues is really in, say, a major key, but we borrow the minor i chord to get the ♭3 and the ♮11.

- Blues is its own unique form of tonality with its own rules of dissonance and consonance. And while it may have sounded dissonant to Mozart, because we have been exposed to blues influenced music for over a century now we have grown used to how it sounds and have accepted its unique rules of harmony as a parallel system to the Western rules of harmony.

Personally, because of the history of the blues and how it arose from uneducated non-European musicians, I think the last option is the best explanation. The Blues doesn’t sound ‘wrong’ and ‘dissonant’ and unpleasant. But it also doesn’t sound in a major key with borrowed minor chords or in a minor key with borrowed major chords. In fact, because of the nature of microtones, it’s possible that an out of tune ‘blue 3rd’ could have been in between a Maj3 and a min3 and thus be neither Maj or min. This is not to mention the fact that because we use equal temperament, our notes are already out of tune.

The Blues sounds interesting and pleasant and good. It doesn’t sound dissonant or like it’s breaking the rules of harmony. It sounds like it has its own internal logic, its own internal rules. The Blues is its own tonality, developed outside the West, to which we have become familiarised and accustomed. Tonality and Functional Harmony was only really created in the 1600’s. Before this time all music was modal. So new harmonic systems are occasionally created and we do get used to them. An equivalent thing happened with the Blues in the early 1900’s.

How to Play Blues Piano

Now after all that theory and history, let’s talk a bit about how to actually play some Blues Piano.

The Blues is a very iconic and distinctive genre that relies heavily on cliches, patterns and licks. In order to play a Blues solo, you need to be able to play at least some of these cliches. For this reason, I have created a Blues Piano Cheat Sheet that gives you everything you need to know to start playing some Blues Piano, including – Left Hand Patterns, Scales, Soloing Techniques, Turnarounds, Licks, and an example solo. All patterns are written in the key of C.

To download the Blues Piano Cheat Sheet: Click Here. The video below will demonstrate how to use this cheat sheet to learn to play the Blues.

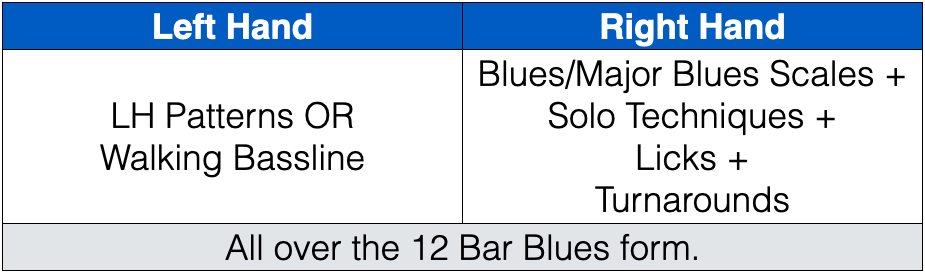

In short, to play Blues Piano you need to do the following:

- Left Hand: Should play a left hand pattern/ostinato or a walking bassline

- Right Hand: Should combine Blues scale or Major Blues scale runs, bluesy soloing techniques, bluesy licks, and a few turnarounds

And this should all be done over the 12 bar blues form.

Again, check out the below video for a demonstration of the above.

Blues Harmony

How to Play Blues Piano